A Buffalo Today, A Thriving Business Tomorrow

My work at Vaya is well underway. In fact, today I reached the two-week mark! The work thus far has been fascinating, not only because of all I have learned about the evolution of microfinance - in India and around the world - but also because of the opportunity I have had to learn from industry leaders with many years of experience, to witness day-to-day operations, and to meet the very clients microfinance institutions (MFIs) like Vaya serve.

My work at Vaya is well underway. In fact, today I reached the two-week mark! The work thus far has been fascinating, not only because of all I have learned about the evolution of microfinance - in India and around the world - but also because of the opportunity I have had to learn from industry leaders with many years of experience, to witness day-to-day operations, and to meet the very clients microfinance institutions (MFIs) like Vaya serve.

My focus this summer will be on individual lending, and by the end of my nine weeks in Hyderabad I should be able to deliver:

- An overview of the existing market, products, competitors, and client needs

- An individual loan product design, associated process flow, and the required underwriting mechanism

- A weighted index to asses clients’ credit absorption, and

- A road map for the execution of the launch strategy

This week I had my first field visit, in the company of two colleagues, to see the group-lending mechanism in action. We traveled roughly two hours outside of Hyderabad, to a small town called Narayankhed. Narayankhed is the first village Vaya ever worked in. It is no coincidence that it is also where Vaya Chairperson and Tufts alumnus, Dr. Vikram Akula, opened his first microfinance branch when he headed SKS Microfinance (now known as Bharat Financial Inclusion Ltd., or BFIL).

My colleagues and I left Hyderabad before the crack of dawn in order to arrive in time to join one of the early morning center meetings. Vaya’s women borrowers come together biweekly at center meetings to confirm their commitment to the group, pay their installments, and plan for future loan disbursements. It was fascinating to see how organized the women were, ready to turn in their groups’ collective installments to the field officer, who expertly thumbed through the cash to verify the amount while using her work tablet to take attendance and record installment figures. At less than 15 minutes, the meeting was as efficient as could be, allowing the women to get to their morning work and home duties without much inconvenience.

After the meeting, I had the opportunity to meet with two of the women borrowers and hear from them about their experience with the lending process.

Vaya borrower Sutina graciously let me take a photo with her and her buffalo. / June 21, 2017.

Sutina (pictured above) recounted how she had saved INR 25,000 on her own (roughly USD 310) and then borrowed another INR 20,000 from Vaya to purchase a buffalo - the price was INR 60,000 (USD 930) but she was able to buy it for 50,000 (USD 775)! She milks about 6 liters from the buffalo per day and sells it to make a few hundred rupees. In a week’s time she has made a significant amount in profits, given that the buffalo grazes and the costs to feed it are minimal. Her confidence and pride in her work is remarkable. In addition to the income she receives through the buffalo, Sutina also mentioned that she often works as a day laborer - this means she goes out to look for work in agriculture or infrastructure projects in her town or other nearby towns. This is the most precarious type of work but can help rural families make ends meet.

I also met with Ghousia, who owns a kirana (small grocery) shop in Narayankhed. With the loan she was able to obtain through Vaya, she purchased a space big enough to set up her kirana and her husbands’ car repair shop - a modest establishment by Western standards but enough space to allow her husband to work from their village, rather than having to travel two hours to and from Hyderabad for work as he once did. Ghousia’s self-confidence shone through - so much so that she complained to me that she wanted me (Vaya) to offer larger ticket size loans so that she could expand her shop! I am working to help make that happen, more so now that I have Ghousia’s grievance cemented in my memory.

Vaya recently went from operating as a bank correspondent (BC), whereby it operated as an agent for a local bank called Yes Bank, to what the Reserve Bank of India denotes as a NBFC-MFI, or a non-banking financial company/MFI. Whereas as a BC Vaya is dependent on Yes Bank to be able to provide funds to its clients, now as a NBFC-MFI, it will be able to do so on its own - cutting loan application and processing times from as much as two months to a matter of days.

The individual lending model that I am exploring will also allow Vaya to serve the needs of mature clients that have gone though various loan cycles and obtained the largest ticket size loan it offers but who still need more capital to grow their businesses; it will also address the concerns of borrowers who - because of the larger ticket sizes and their growing financial literacy and confidence - no longer want to be liable for fellow borrowers through the joint liability group scheme.

For these reasons and many more, crafting an individual loan product is the next logical step in the company’s progression and clients’ growth.

During my trip, I also visited one of Vaya’s branch offices in Narayankhed, to get a closer look at all of the back-end work that most never see. Stay tuned for my next post on it!

Hello from Hyderabad, India

Today marks my fifth day in Hyderabad, India’s “city of pearls,” biryani capital, and its second Silicon Valley. Here are some thoughts, observations, and learnings from the city I will call home for the next two months.

Today marks my fifth day in Hyderabad, India’s “city of pearls,” biryani capital, and its second Silicon Valley. Here are some thoughts, observations, and learnings from the city I will call home for the next two months.

Locals walking alongside one of Hyderabad's main roads. / June 11, 2017

It’s a man’s world.

Men. Men everywhere. Men on motorcycles. Men in rickshaws. Men standing idly on the street. Men in cafes. Groups of men on buses and just about anywhere you look for that matter. The interesting thing is that you’ll find most men in western dress, wearing button-downs or t-shirts and jeans. And the women? The few women you see commuting are almost always in vibrant traditional Indian clothes, sporting comfy kurtas and stylish saris. They are like rainbow sprinkles on the rocky Hyderabadi road.

SLOW: City “under construction.”

The most striking thing about Hyderabad is its stark contrasts, irrespective of the neighborhood you find yourself in. On any given street, you can find an imposing, modern high rise next to an abandoned plot full of piled up stones and rubble, which is in turn next to shacks made of corrugated metal and plastic sheets. Ten years ago, the new “tech city” was non-existent. Today it is absolutely chaotic, but also one of India’s up-and-coming urban centers.

Holy cow (and bull)!

I had heard the stories about how cows are sacred in India, and how they roam about freely through the streets. Still, it never occurred to me that bulls would receive the same treatment. Much to my surprise, on the first day in Hyderabad, I spotted beige cows and jet black, horned bulls wandering about on the side of the street – sometimes alone and sometimes being led by locals. Who knows, I may be spotted at some point swinging my bright red raincoat on the streets of Hyderabad, shouting olé as I dodge a raging bull’s advances.

Everyone is praying for monsoons.

Expecting to melt away with the hot Indian sun, I have been pleasantly surprised to find relatively mild, warm weather. With monsoon season underway, the first rains poured down, cooling the city. A close friend told me,

“You’ll see, everything here depends on how good the monsoons are. Good rains mean good crops – and low inflation.”

The same day, a colleague related the monsoon to microcredit loan default rates: in years of good monsoons, rural farmers have plentiful harvests and loan repayment rates are near 100%. In bad years, however, default rates rise – this is one of the risks that microfinance firms must factor into the risk premiums for their loan products (and one of the subtle aspects I will have to consider for the next two months).

I couldn’t be more excited to work at Vaya FinServe this summer. I’ll be helping them think through how they should launch individual loans to enable many more Indians at the base of the pyramid grow their businesses and lead better lives.

Providing market access to handicrafts artisans in India

I interned in the summer with Access development services in Delhi and Jaipur, India. Access is a livelihoods organization working with 10000 artisans across the country. They do this through a network of 300+ full time employees spread across major states in India where they work on the ground with artisan clusters.

I interned in the summer with Access development services in Delhi and Jaipur, India. Access is a livelihoods organization working with 10000 artisans across the country. They do this through a network of 300+ full time employees spread across major states in India where they work on the ground with artisan clusters.

The artisans are mostly nomadic in nature and lack formal education/ training. They have been trained over the years by a combination of trial end error and passing on of skills across generations. Understandably, they are not connected to formal banking systems and also have poor working conditions. For example- for work involving lac beads, the artisans need to sit around a mini fire kiln and work. This combined with a 49 degree Celsius outside temperature make it real difficult for the people to work.

Access works towards connecting these people to the mainstream by linking them to banks, providing training and development and providing access to different markets.

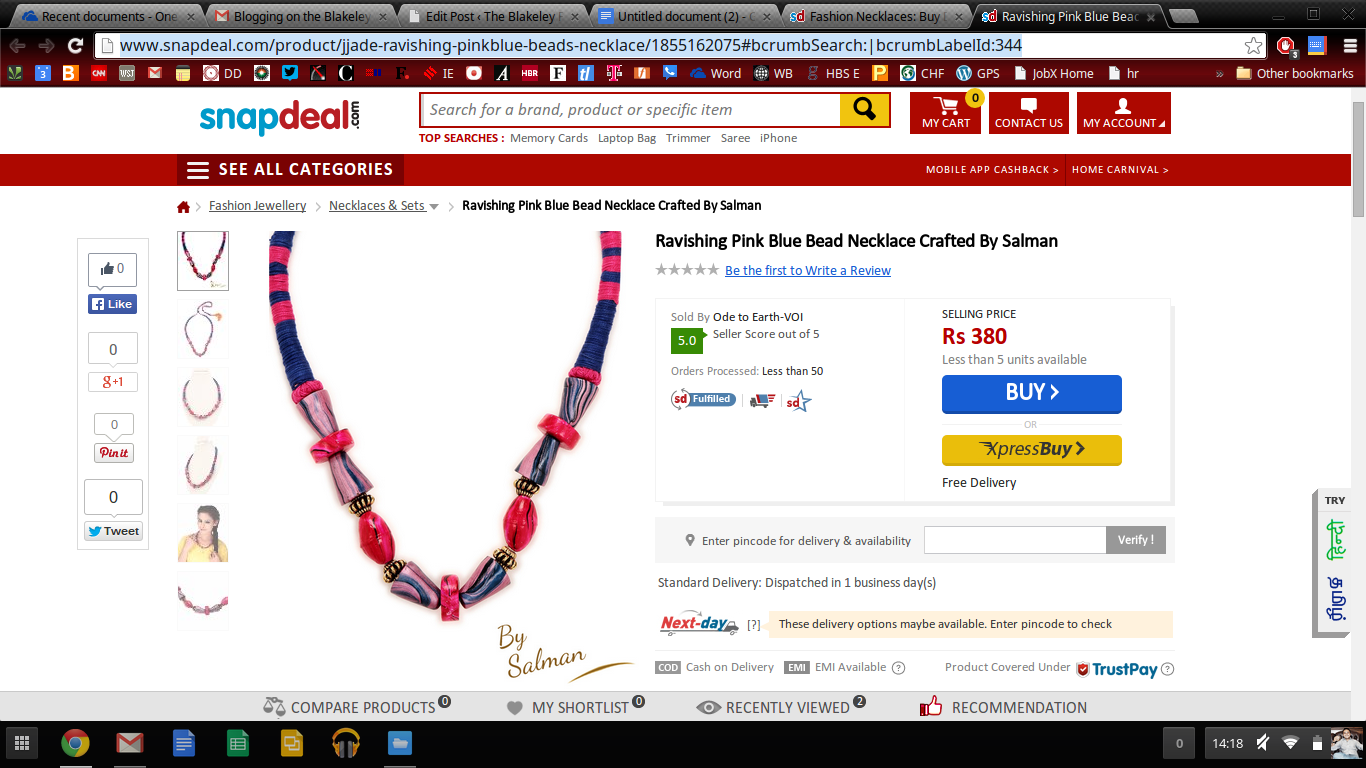

As part of my internship I focused on the market access bit. Streamlining the production and quality process and tie ups with major e-commerce networks followed. Recently, the products were launched online under the brand JJADE which stands for Jaipur Jewelry Artisans Development Project. Artisans were individually identified on their creations on the lines of designerwear to provide them with a sense of belonging and motivation.