Finally! More Photos from Chad

The charcoal production site: The manioc paste is then mixed with carbonized agricultural material. This material was left out in the rain and the team was trying to dry it out.

Here is the sack of manioc (also known as cassava or yuca). The chunks in the picture are first pulverized into a flour and then flour is stirred into a big pot of boiling water until the mixture becomes a sticky paste.

The charcoal production site:

The charcoal production team:

Here is the sack of manioc (also known as cassava or yuca). The chunks in the picture are first pulverized into a flour and then flour is stirred into a big pot of boiling water until the mixture becomes a sticky paste.

The manioc paste is then mixed with carbonized agricultural material. This material was left out in the rain and the team was trying to dry it out.

Pouring the prepared binder mix for another batch of briquettes:

The carbonized material is mixed with the binder and then pressed into these molds. The team can produce about 1300 briquettes in a 7.5 hr workday.

Drying the briquettes on a tarp. The thin plastic tarps costs about $50 each in Chad.

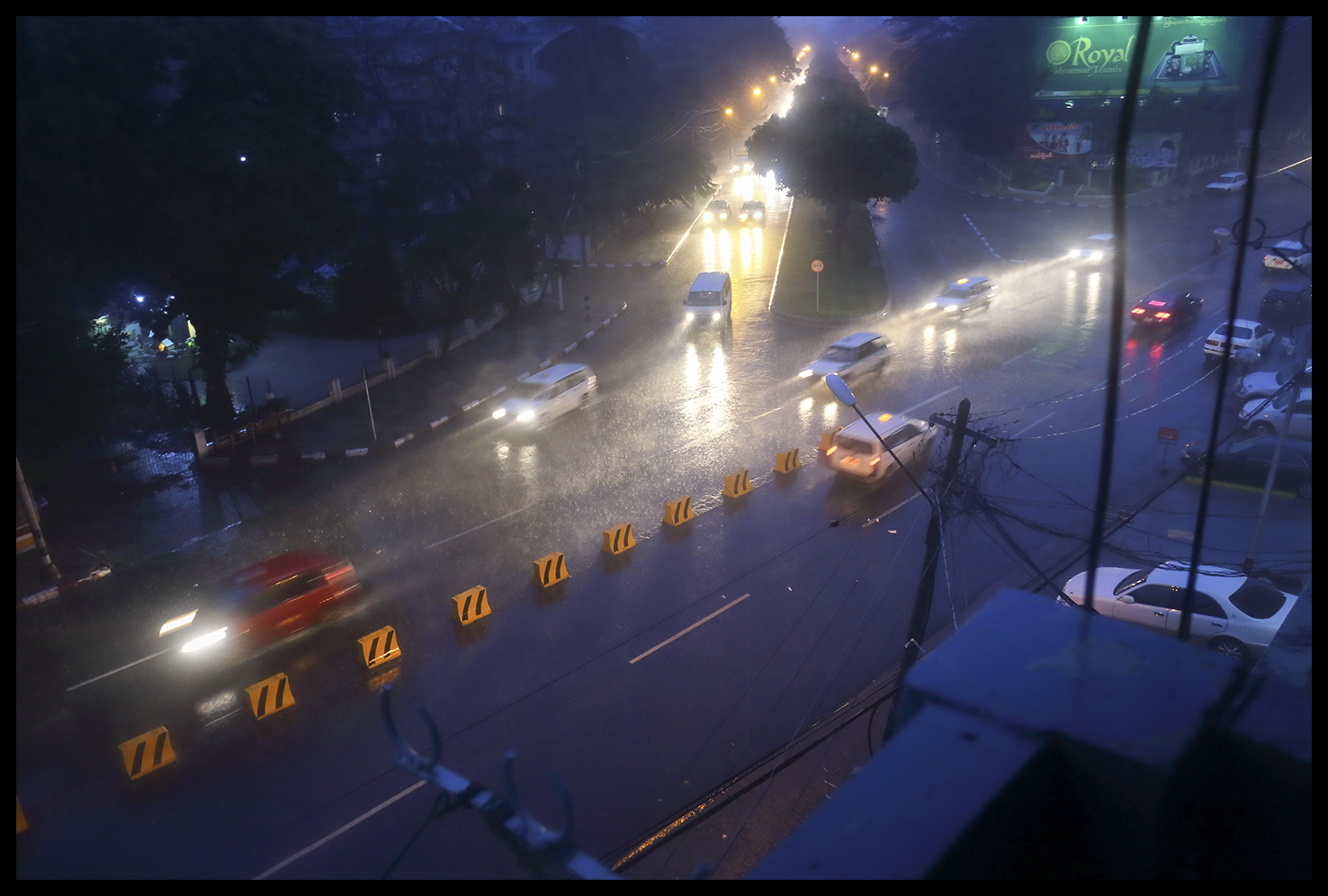

Quick! Move the briquettes before the storm hits! Deluge occurred minutes later...

Taking measurements of wood charcoal to compare with our briquettes.

Eating food cooked with the eco-briquettes.

Within sight of our charcoal production, locals passed by riding bicycles with huge bags of charcoal strapped to the back. They smuggle charcoal into the city by dirt roads and paths to avoid the checkpoints on the main roads.

David talks business, management, and strategy with Aquilas, the Chadian National Coordinator. The daily long conversations were critical for building relationships and talking through the challenges together.

David and Ghislain logging onto the new laptop donated to ENVODEV by a great friend in Boston. Thanks Nate!

Studying the design of the rammed-earth mold. We discovered several errors in the instructions. Thankfully we were able to adapt.

Aquilas had previous experience ramming earth. He put us all to shame! My hands were covered in blisters after an hour of swapping turns packing the clay.

Some of the local kids thought I was Chinese. The only non-Africans they had ever seen were the Chinese oil workers.

The finished rammed earth stove! We finished this on the last day in Moundou. Grateful to have finished one before we left!

ENVODEV's full-time staff: Ghislain, Aquilas, and David.

Ghislain and I posing for a picture in Moundou. It was so great to get to be a part of the team!

Myanmar: Building Hope from Rubble

[p]U Aung Zaw, whose business prior to April 2008 employed 43 workers and could produce anything that you could draw, from elaborately colored platters to wine decanters with cleverly placed pockets for cooling ice. A simple factory built from timber and sheet metal didn’t meet the standards of the 1st world, but served many businesses, organizations, embassies, and individual homes throughout Myanmar. [/p]

[p]However after Nargis the plant was destroyed, there was little hope of rebuilding and zero support for small businesses or industries impacted by the disaster. The kiln which had been the centerpiece of the factory had been cracked in the storm and because of the building’s collapse, was almost beyond repair. Hundreds of shelves of finished and nearly finished products were scattered around more then an acre of jungle, itself now reduced to a chaotic jumble of branches, frawns, timber, and sheet metal. Charcoal, which had been the primary fuel source for the furnace, climbed rapidly in price to nearly 12 times the 2008 costs. And with no income most of the skilled glass workers quickly left the compound to work abroad.[/p]

[p]In addition a larger problem looms with the remaining former employees. For families that didn’t leave, they took up residence on the factory’s property and have taken work at other businesses or work as day laborers. Having lost all paperwork in the cyclone, U Aung Zaw could not prove the title to his land, and faced both social and physical resistance when he voiced his resentment of the small shanty town that has taken over part of the old factory grounds.[/p]

[p]Small fights have broken out, and now as they come home former workers and their families will take items from the piles around the old compound to use or re-sell. U Aung Zaw refused to speak about the subject further given his fear of physical harm and retaliation, particularly if he were to push to rebuild the factory or to have the squatting homes removed.[/p]

[p]As a testament to U Aung Zaw and his family’s ingenuity, it became apparent that slowly returning tourism might offer some small income. So to provide for the family’s income U Aung Zaw would allow visitors to wander the grounds of his compound, digging through deep piles of frawns and mud to unearth largely unbroken glassware. A literal treasure hunt would turn up anything that had been in production prior to the cyclone, and for those who are more creative, U Aung Zaw’s family would cut down, polish, and even fuse pieces of glass to make entirely new items.[/p]

[p]This leaves me asking a question I really don’t know how to answer: Regardless of funding or resources, how do you work through suffering, trauma, and loss? How do you find a way to support and assist when an internal desire has gone out?[/p]

[p]Many of you who know me are probably aware of how much I’ve considered this question of behavior and psychology to be of crucial value. I imagine that to make an impact in these situations it would need to be of central importance to any approach to provide support and must specifically begin with conversations and a lot of good listening. And still, sadly, at times it seems you just have to accept a result and mitigate pain and suffering by moving on. But where does that cut off exist?[/p]

[p]I’ll be visiting the former factory again with a local Burmese art gallery/social enterprise, and will update as the story unfolds.[/p]

A Village Stay in Burkina Faso

While I've been busy at work in Ouagadougou, capturing many of the interviews I conducted with beneficiaries of the Agricultural Development Project of the Millennium Challenge Corporation Compact with Burkina Faso, and writing reports from my field visits (more on this soon), I wanted to share with you all some photos from a recent visit to a village in western Burkina Faso. Last weekend, I had the good fortune of accompanying a co-worker to his village near Doudou, where he served during his time as a Peace Corps Volunteer. Doudou is approx. 150 km from Ouagadougou, near Koudougou, the third largest city in Burkina Faso (after Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dialosso). ("Dougou", I recently learned, means "ville" or town).

While we only stayed a night, it felt like a long weekend, filled with special moments: sharing a meal with former counterparts, visiting different homes to pay our respects, inspecting a newly installed water pump, sleeping under the stars, and strolling through the market in Doudou on Sunday.

Sharing an incredible feast with my co-worker's former counterpart, Moises

Visiting the local market in Doudou on Sunday (Photo credit: Chris)

The local language, Lyele, was as enjoyable to learn as Wolof, and while I only was able to pick up a few phrases, I know fellow Star Wars fans would have been absolutely enchanted.

Me: "Aja?"

Woman in Market: "Jawane!"

Literally, this means, "Do you have the force?" and the response, "Yes, I have the force!"

Many come to the market on Sundays after church (usually a 3-4 hour service), and sit under the wooden stalls for some shade, drinking dolo, the local brew made from fermented millet, and catching up on the local gossip. The dominant ethnic group in the area is Gurunsi, of which most are Christian.

One of the best parts of our stay was our lodging. Traditional style homes are large adobe constructions that have a small wall around them. They can typically hold at least a dozen people, usually more. This particular encampement, is one of four in Burkina Faso, and is a community-organized and supported endeavor. Profits go towards local projects, such as a local primary school, an adult education center, and family planning classes for women. The manager of the compound also had a strong agro-ecological philosophy, detailing why many in the area were committed to organic compost and avoided using chemicals, as the community had already experienced the negative health side effects agrochemicals could cause if not properly applied.

Due to the heat, we placed our beds outside and it was a smart decision. The stars at night were absolutely incredible.

All in all, it was an incredibly enjoyable weekend, and a nice break from the bustle of Ouaga.

A few more photos from our village stay:

Exploring the entrepreneurship trail in Lima

Even before I set a foot in Lima I was warned not to expect to enjoy a sunny summer, that in fact the temperature was going to be constantly around 60°F (15°C) day and night and with a humidity of 85% or more. Unfortunately that was not a lie! Almost every day is cloudy and somewhat cold, nothing compared to Boston (of course), but still quite chilly.

However, I was never told about and was not really expecting to see, so many parks, full of flowers and with very well taken care lawns. Public spaces are a high priority for many municipalities in Lima and Peruvians (as well as Peruvians cats!!) do take advantage of these spaces. Internet is even offered for free not only in parks but also in metro stations and many cafeterias and restaurants.

I have been studying about the history of its public transportation because I have been helping to organize an event where understanding Lima’s future infrastructure plans is very relevant. Can you imagine a city of more than 8 million people with a single metro line that crosses the city from south to center? The center to north leg is not even completed yet (it is part of the second phase of the metro line number 1).

However, besides the unfinished metro they do have a modern BRT system, which is also only running south to north. In my experience, the BRT has proven to be very useful and fast. The city of Lima, similar to others in the world, has heavy traffic almost at any time of the day or night.

Infrastructure plays a very relevant role in the developing of an entrepreneurial ecosystem. My interest in understanding more about this particular ecosystem is what brought me here to Lima in the first place. So I was initially concerned about how is that an entrepreneurial spirit can flourish in a space that is not very well connected.

It did not took me long to be impressed about the Peruvian entrepreneurial spirit. It was first palpable in the quality and diversity of its cuisine (they even have made a fusion style between Peruvian and Chinese cuisine called “chifa”). Not only every dish I have tried is full of flavor but also it is admirable the care Peruvians put into the decoration and image of their restaurants, even at the small places that only offer set meals. Peruvians are very proud about their cuisine and are not shy to show it in every detail, the menu, the dish presentation and even the boxes or bags used for take away meals.

I am working now in learning how could this entrepreneurial spirit be spilled in other realms and not only in the food sector.

The people I am working with want to bring The Hub brand to Lima, because they believe there is urgency for a collaborative space that is able to offer mentorship and financial support for the new wave of social entrepreneurs that are starting to emerge.

This is a live project! I will let you more about it in a few more weeks!

Let me just share with you some amazing landscapes of the city of Lima.

This archeological site (Huaca Pucllana) is located in the middle of the city.

Myanmar: a few stories

[p]The research we’ve been conducting on financial habits in rural and urban communities has moved relatively smoothly despite several hang-ups, which I’ll describe in a later post.[/p]

[p]We’ve encountered some truly incredible people, and in every case our interviewees have been generous with their time and insights regarding how they approach finances in their lives. As we’re not building a quantitative picture, instead relying on the personal observation and insight from individuals, we’ve had more work to do in sifting through our conversations and giving an order to what we’ve heard and learned. Here are a few profiles of people we’ve talked to so far.[/p]

[p]Early on we spent time with Daw Boke who jointly operates an apartment rental service and a bus ticket sales business from her home with her husband. Aunty Boke, as she’s affectionately known, has slowly built up her business in downtown Yangon from the home she’s occupied for the last 40 years. As buildings grew out of the old traditional wooden homes – first bland socialist era apartments, and now glitzier structures built by Chinese, Thai, and Singaporean investors – she has grown extremely familiar with the property and apartment owners in the area. In Myanmar it is still illegal for 100% foreign ownership of property, so she her business has been entirely with Burmese individuals.[/p]

[p]Over the last two years of the reform Aunty Boke’s business has grown rapidly. Over five years ago apartment turn over and rentals were relatively slow and she relied on her landline phone as a second source of income. Most homes don’t have phones so private phones that are set on the sidewalk on a small children’s table, or beside a front door effectively become public phones for a small fee and can bring in much needed extra money. However that business all but dried up for Aunty Boke over the last two years as cell phone use has grown rapidly.[/p]

[p]Now Aunty Boke’s apartment business provides the lion’s share of income by connecting individuals with apartment owner’s spaces. However her reputation and length of time working in this field has made her a familiar source for successful rentals thus allowing her to work directly with apartment owners, and earn a larger portion of the profit from a rental. Normally the renter's fee is divided between anyone who has interacted in the process of renting an apartment – for example if you unlock the door for a client or show them where the apartment is you get a certain percentage of the renter’s fee. Interestingly too all transactions for rentals occur in cash. If Aunty Boke helps sell an apartment – at shockingly high prices now as the Myanmar real estate market has exploded – the buyer will meet the owner at the apartment with hundreds of millions of dollars in cash, carried up dimly lit stairs in trash bags. This process is surprisingly easy and completely normal. Services exist for carting large volumes of cash around – a curb side pick up and drop off service. She told us stories of how people would forget bags of cash in taxis, or on curbs, would walk up to their apartment realize their error, and run back down to find the bags sitting in the same place, or the cab driver trying to find them to return the bag. This does not mean crime doesn’t occur – she noted that just several days prior a car was broken into on her street and emptied of its contents (though there were no bags of cash inside).[/p]

[p]Despite a high cash system of transacting in real estate, and the use of a bank, Aunty Boke confirmed a trend we’ve seen repeated in a wide range of economic segments -She invests in a friend's business (car parts manufacturing) just so she won’t have large volumes of cash in her home or in the bank account (which she only opened 3 months ago). While she does use banks, multiple economic crisis and the collapse of several former banks leaves her wary, so she prefers to bank with the government banks that have more state guarantees than the private ones.[/p]

[p]When looking at financial habits, after 60 years of military rule it's impossible not to run square into those who’ve suffered under that reign. Political prisoners have to transact, make money to survive, and try to live as best they can given a system stacked against them. But what is striking is the perseverance and generosity they demonstrate in overcoming years of imprisonment. In another encounter we met with a former political prisoner, Ko Kyaw Soe, who after his release from prison, worked as a taxi driver, and provides interest free loans to other former political prisoners to start small businesses.[/p]

[p]Ko Kyaw Soe is by no means rich. He lives in a small second floor apartment that over looks the street where he parks his car. Out of prison a year ago, he still must take time off from driving due to kidney injuries he sustained from torture by prison guards. But for this exact reason he and two other former political prisoners now use their incomes to provide loans to those still coming out of prison. By saving up the equivalent of a little more then $500 they are able to help the discharged political prisoner start a small business or place a rental down payment on a taxi. They then have a year to repay the amount.[/p]

[p]Cars, which have been notoriously expensive, still are commodities that most taxi drivers do not actually own. However prices have come down significantly – only three years ago a basic Toyota that could cost $600,000 due to the import license and drivers permit, now are down to $100,000. Ko Kyaw Soe owns his own car but most of the prisoners starting out must pay for a daily rental fee, gas, and larger monthly costs to the car owner.[/p]

[p]Ko Kyaw Soe, given his political status, cannot directly transact in the bank account system. When arrested in 2007 he lost a large amount of his money to the government. Instead he keeps the cash in his car – safe compared to his home, which has seen frequent ‘visits’ by the police. Here too, all of his transactions are made in cash from the rent of his house to providing funds to the other prisoners. Cash, though at risk of theft, is liquid and easy to transact in, which is crucial in a field that has a high cash turnover rate like the taxi business. Despite the risk, he hopes that by providing loan to other former political prisoners they will provide a leg up for those have been stigmatized by years of imprisonment.[/p]

[p]I’m hoping to post more profiles of people we’ve interviewed and some photos too if possible. Eventually we’ll have a few more concrete ideas about just what issues people face, how they adapt, and some factors unique to Myanmar’s context.[/p]