Magnifying the Magnet

A lot has already been written about the emergence of tech hubs across Africa. Many have attempted to map major players in the growing ecosystem including Julia Manske in a report for Vodafone and Tim Kelly of the World Bank. By the end of the summer, I will have had the opportunity to visit five major labs including the iHub, Nailab, and m:lab in Nairobi, the Hive Colab in Kampala, and Jozihub in Johannesburg. With each visit comes a better understanding of how these open workspaces, tinker shops, and innovation incubators work.

A lot has already been written about the emergence of tech hubs across Africa. Many have attempted to map major players in the growing ecosystem including Julia Manske in a report for Vodafone and Tim Kelly of the World Bank. By the end of the summer, I will have had the opportunity to visit five major labs including the iHub, Nailab, and m:lab in Nairobi, the Hive Colab in Kampala, and Jozihub in Johannesburg. With each visit comes a better understanding of how these open workspaces, tinker shops, and innovation incubators work.

While most tech hubs operate as independent institutions, many are connected through a larger umbrella network called AfriLabs. According to their website, “AfriLabs exists to support the growth of communities around African technology hubs and to encourage expansion of the network by providing tools and resources for new and emerging labs.” It is exciting to see AfriLabs link best practices and best people across countries and disciplines, connecting disparate dots throughout the continent.

But despite this environment of excitement, I continue to encounter a persistent question: Are these labs actually creating an impact? Thanks to the support of programs like Fletcher’s Blakeley and Empower Fellowships, I have used part of my time this summer to unpack this complex question. Measuring impact—whether through job creation or national economic growth—is challenging. Connecting specific data points with the establishment of a tech hub is thorny at best, and therefore, I will not claim to make this link. At least not yet. Instead, I can tell you that my initial research points to something less measurable but certainly not less meaningful: Tech hubs in Africa catalyze community. They serve as a magnet, drawing in sharp people with promising ideas. As iHub founder Erik Hersman told me during an interview a few weeks ago, “The iHub was always designed to be a community space first. When you put cool people, in a cool place, cool things will happen.”

I agree with Erik. In a previous blog post I underscored my belief that tech hubs act as community fabricators. Similar to interest groups or neighborhood associations, hubs and their associated events offer techies room to connect and grow. For Jason Eisen, the CEO of a Kenyan transportation startup called Maramoja, a recent pitching competition and conference provided this space. He noted, “Pivot East helped us pick up our heads and see the full potential of Kenya’s tech ecosystem.” Jason went on to note that events like Pivot and places like the iHub “allow the tech community to interface with the larger community.” At the end of the day, community remains at the heart of the tech hub success story.

Fine. Community is important, but what lies ahead? Personally, I hope to see two major trends—a new emphasis on business skills and more opportunities for hands-on management experience at established multinational corporations. During discussions with several coders, investors, and hub managers I kept hearing the same thing: We must build entrepreneurs with applicable business skill sets. Today, many African tech startups lack basic skills critical to running a functioning business like understanding financials, nimbly negotiating a contract, and leading a team. I wrote a recent piece for the Fletcher Forum that discusses this skills gap.

Second, Africa’s tech labs need to establish stronger links with known employers. Ideally, I would love to see big names like Apple, Microsoft, Samsung, and Techno hiring their local workforce out of Africa’s tech hubs. In turn, these hubs should establish a career counseling service similar to Fletcher’s Office of Career Services. This carve-out could prep community members for case interviews, help them whip up one-page resumes, and connect them to hiring employers.

At the end of our interview, Jason said something that really stuck with me. “Today hubs have a huge focus on entrepreneurship—but a limited focus on placing people into professional jobs.” Moving forward, let’s ensure that tech hub incubatees have the right balance of tech skills, business acumen, and actual corporate experience to fuel positive change.

Mwiriwe from Rwanda

Greetings from Kigali, Rwanda! My name is Heather LeMunyon and I’m a Master’s degree candidate at the Fletcher School at Tufts University in the US, where I’m concentrating in international business relations and development economics. I’ve been in Rwanda for about one month now, and have been gaining incredible experience diving head-first into the challenges and opportunities that the Rwandan economy and its businesses have. During the summer break between my first and second years at Fletcher, I am working with the African Entrepreneur Collective (AEC), a non-profit business accelerator for young, growth-oriented entrepreneurs in Africa to create jobs for the unemployed in their communities. To reach these goals, AEC works through local business development partners in order to best tailor services to the communities of each country. In Kigali, I am working through AEC’s local Rwandan partner, Inkomoko Entrepreneur Development, a full-service business development firm focused on developing start-up, small and medium enterprises to grow them into effective businesses.

In Kinyarwanda, inkomoko means “the source” or “origin.” Inkomoko is industry-agnostic, meaning that they do not focus their business development services for any one particular sector. However, their clientele is fairly representative of the Rwandan economy – about 40 percent of their clients work in agriculture or food processing, with other large sectors being construction, professional services, information and communications technology (ICT), and energy. My role with AEC through Inkomoko has been to work directly as a short-term consultant and business mentor for two of their clients, HPS&B, a rice processing company, and Hollanda FairFoods, Rwanda’s first potato chip company. My background is in agribusiness development, so the opportunity to work hands-on with two of Rwanda’s promising post-harvest agricultural processing businesses has been incredible.

The work that AEC, Inkomoko, and their clients accomplish on a regular basis is quite impressive. On my first day in the office, I read an article on the front page of The New Times, one of Rwanda’s national newspapers, on the impressive business growth of one of Inkomoko’s clients, Green Harvest, a company producing hot sauce and spices. Four out of the fourteen national finalists for Rwanda for the international SeedStars Business competition were Inkomoko clients, one of which was Hollanda FairFoods. I was honored to be here for the last day of Inkomoko’s fiscal year on June 30 when all of their nine full-time staff celebrated the 80+ new clients they brought on this past year and the impressive successes many of them have had in growing their businesses.

My work has been busy, rewarding and fun! My assignments thus far have included updating market analyses and financial projections for both HPS&B and Hollanda FairFoods; liaising between clients and international investment firms looking to invest in emerging markets, particularly in Rwanda; collaborating with my clients to develop data collection mechanisms for market information; coaching Hollanda FairFoods on its first pitch to international investors; compiling funding opportunities for Rwandan agribusinesses into a centralized database; and analyzing Inkomoko’s metrics for organizational development.

Life isn’t all work, though. The Inkomoko staff work incredibly hard but also know how to let loose. Last weekend, we celebrated the end of the fiscal year with a day-long goat roast, complete with about 100 brochettes (kebabs) for all of us by the end of the night. They’ve also had a bit of fun teaching me words in Kinyarwanda as I slowly learn a few phrases in the language. Living in a large group house with AEC’s other short-term business mentors has been fun as well—a great platform for getting to know other graduate students and young professionals interested in entrepreneurship in emerging markets, and great for planning weekend trips to explore Rwanda outside of Kigali.

Time is already going by so fast! I’m looking forward to meeting up in Uganda this coming weekend with some this year’s other Blakeley Fellows in East Africa, too – Anisha Baghudana, Manisha Basnet, Owen Sanderson, and Anjali Shrikhande. More updates to come during my next few weeks in Rwanda – until then, many, many thanks again to the Blakeley Foundation for making all of this possible for me, and enjoy the photos of life in Rwanda thus far!

The Entrepreneurial (and Fun!) Ushaverse Family

“How’s your summer going?” I have been asked this question countless times from friends, family, and former colleagues since landing in Nairobi four weeks ago. This open-ended inquiry is usually followed up with, “What’s Ushahidi like and how are the people?” While I cannot claim to be an expert, the last month working in the Ushaverse (the collection of enterprises and initiatives launched by Erik Hersman, Juliana Rotich, David Kobia, and others) has provided me with a healthy taste of life in Kenya’s magnetic entrepreneurial tech scene. And I am happy to report the experience has been incredibly positive.

“How’s your summer going?” I have been asked this question countless times from friends, family, and former colleagues since landing in Nairobi four weeks ago. This open-ended inquiry is usually followed up with, “What’s Ushahidi like and how are the people?” While I cannot claim to be an expert, the last month working in the Ushaverse (the collection of enterprises and initiatives launched by Erik Hersman, Juliana Rotich, David Kobia, and others) has provided me with a healthy taste of life in Kenya’s magnetic entrepreneurial tech scene. And I am happy to report the experience has been incredibly positive.

Over the last six years since graduating from college, I’ve worked for a number of different organizations. Each one maintains a unique feel. Some are massive, with thousands of employees seamlessly operating around-the-clock. Others are smaller in shape and more defined in purpose. A few are global with networks that stretch from Boston to Bangalore. Ushahidi manages to straddle the line between a local outfit and an international enterprise. It is global while remaining lean and agile. This is a beautiful thing. Despite having less than 30 full-time employees, Ushahidi manages to operate worldwide. There have been over 60,000 Ushahidi deployments in 159 countries since Ushahidi launched in 2007. Enabled by a combination of open-source platforms and whip-smart staff members, Ushahidi has unquestionably created an international impact and recognized brand.

So what is the secret sauce that brings this small yet potent cohort of bloggers, coders, policy wonks, and ultimately leaders, together? Passion and good humor. Consider this: Every Monday the Ushahidi team logs onto Hipchat and connects to a global conference call. The weekly touchpoint provides an opportunity for Ushaverse employees to inform their colleagues about product breakthroughs, solicit advice on thorny deliverables, and advertise upcoming events. But besides these professional updates, the weekly call offers a chance for our remote team to connect. This week’s call included way too many bad puns, a bounty of baby pictures, and epic travel stories from the field. At first glance, these virtual updates seem silly (and some may say unnecessary); but I believe they help bind together a remote team spread across time zones. They represent Ushahidi’s dedication to fostering a positive and productive culture that’s not afraid to have fun.

Last week marked the halfway point of my summer with Ushahidi. Simply put, the time has flown by. In four short weeks, I have mocked up a business strategy for a new Ushahidi product, spoken at Tech4Africa in the iHub, ran a half marathon alongside rhinos with a dozen of Ushaverse colleagues, and blogged nearly every other day. In true Ushahidi form, my midway mark was celebrated with a bit of pomp and pageantry. At approximately 3pm, Erik Hersman strode into the batcave (our co-working space located below the iHub) holding a Crowdmap sweatshirt. With a firm handshake and a few snapshots, I was bequeathed a gray hoodie. While only a temporary member of the Ushahidi team, I felt welcomed (and perhaps slightly awestruck). It is this type of camaraderie that drives the Ushaverse forward—and I am very, very proud to be associated with such a path breaking, human-centered organization.

Race, Inequality, and Policy Attempts to Address it in South Africa

South Africa is a truly remarkable place with a rich history that holds lessons for the rest of the world in the political, economic, and cultural realms. Because of the country’s history with apartheid, and so in this post I will speak to the ways I have encountered the race topic since being in SA – as race touches every aspect of life here.At Endeavor, a high-impact accelerator, my project is to help improve their program that focuses on black entrepreneurs – a good cause. Yet, the implementation of affirmative action in SA through BBBEE (Board Based Black Economic Empowerment) legislation has had some interesting effects. The scheme is highly complex, but I will touch on some of my key learnings so far. First, firms must donate a portion their profit to Enterprise Development (ED), which are programs to help develop black owned businesses. This has led to a boom in the business development services (BDS) field, which Endeavor is in, with more than 200 organizations seeking to support entrepreneurs – and as such get their hands on ED money. Ironically, the byproduct is that there are too many service provides and not enough good entrepreneurs and money gets wasted on people, often with people using BDS as a way to source a job, and often participating in several incubators without ever really starting something. As a result, capital in the jobs starved SA economy is wasted. Second, there are sort of ‘quotas’ for organizations to have black leadership and employees. However, the education system is terrible in SA with not enough talent to meet businesses’ needs. Furthermore, strict labor laws make it hard to fire people. As a result there is a booming labor brokerage industry, which act like temp agencies, that distort the talent in the job market, wages, and keep unemployment high. Over the past few weeks I have spoken to several professionals (black and white), often in the financial services industry, who have given me examples of issues that they faced. A highly educated young black stock broker talked about his boss without a university degree continuing to rise, but him unable to because he is there to fill a black quota, but at the least cost to the firm. Meanwhile, a white commodities broker spoke to me about his year working with a large bank under a temp contract but could not get hired because the bank needed to meet its quotas. It is amazing how openly people discuss race in SA. They have shed the stigma we in the US ache over using the words black, white, and colored to describe people. There are indeed large economic imbalances in society, often along racial lines. BBBEE is an interesting experiment at socialist redistribution, but it just might undermine the economy and shrink the economic pie for all. As the world wrestles with the topic of inequality thrust to the forefront of the global political debate by economist Thomas Pinketty, we should look to South Africa for lessons. Furthermore, too often politicians enact policies that have unintended consequences and then lack the willingness to follow up to improve those policies. This lack of humility reminds me of a question a friend asked me when I was young -- “Would you rather be happy or right?”

Below are a few pictures showing the "two worlds" that exist in SA. From a world class rugby stadium and the ultra modern stock exchange, to the dirt streets of a slum 15 minutes away.

Kibera, Nairobi - First Visit

Hello again from Anisha in Nairobi!

In this post, I want to give you a descriptive feel of Kibera, Nairobi's slums.

I have visited Kibera twice in the last ten days, the first time for a tour and the second time to conduct interviews. This post is about my first visit. Kibera rivals Dharavi - Mumbai's slums that I am familiar with - in every possible way: entrepreneurial energy, poor living conditions, environmental pollution and a sparse cheerfulness that defies logic but is not uncommon among people who live on little.

I was escorted by Abasi (fictional name; I picked the first one I saw on a Kenyan baby names’ page), the young 26-year old leader of a Kibera community non-profit that makes money for its members through recycled products. There are two Kiberas in Nairobi city, and seven villages inside them. They are divided by “trees and rivers,” as Abasi said. The rivers are genuinely small drains, and nothing more. The trees - only years of living in Kibera can turn them into landmarks. A railway track separates the posh neighborhoods of Kilimani and Kileleshwa and a golf course from Kibera. This railway line goes all the way into Uganda, and was built during colonial times (in 1899). Even today, trains pass through every four hours, I am told, carrying passengers into the neighboring country.

Abasi and I walk and talk, and I wonder if I should be taking pictures to document photographic evidence for my research. Seems wrong. Our first stop is a garbage separation point where some of Abasi’s employees are busy at work. In a nearby hut, Abasi shows me a few paintings members of his organization have made using recycled materials. He explains that 50% of money they make on each painting goes towards operational costs – marketing, selling, buying ‘raw materials’ (that’s waste basically) – and the other 50% goes to the skilled individual (artisan / artist / designer-tailor / handicrafts man) who creates the final product. This is too good to be true, but seems to work.

A little more about Abasi at this point. Abasi is from Kibera. His parents hail from the western part of the country. They moved to Kibera in the 60s, after Kenya gained its independence in 1963. Around this time, Nairobi held the new promise of many lucrative jobs and saw droves of people immigrating from villages. Kibera was one of the cheapest parts of the city to find housing. Abasi was born and brought up in a Kibera house where he lived with his seven siblings and parents. He lives in Kibera today too, but now with just one brother and parents as the rest of his siblings are married and have their own families. Abasi’s folks belong to the Luhya tribe, which forms the majority in Kibera. Interestingly, Luhya is not the largest tribe in Nairobi – that’s Gikuyu (pronounced Kikuyu), the one that my taxi driver belongs to. According to Abasi, Luhyas are gradually taking over from Gikuyus all across Nairobi as they are having more babies. I don’t know how much of this to go by, as a lot of tribe-related information I get is conflicting and I can’t find a reliable resource online either.

Abasi completed his undergraduate education in community work at a local private university on a scholarship. This voluntary initiative takes up 40% of his time. He spends the remaining 60% on odd jobs that provide for him. He wants to open up a recycling plant in Kibera soon. It requires significant capital, around USD 10,000, and is therefore not a foreseeable reality. So, Abasi would rather do a master’s in development studies in Nairobi or outside the country on a scholarship for now. I ask him, what do you want to do ten years from now. He says, definitely work with people in Kibera to improve incomes. I ask if he thinks the slums will still exist ten years from now, and he’s pretty confident that they will be around. Like a dog with its tail firmly between its legs, I walk into the heart of Kibera with Abasi.

I decide to be brazen enough to get my phone camera out and capture some of what I see. I am taking pictures mostly of green-painted M-pesa agent shops and “Lipa na m-pesa” (Pay with M-pesa) stickers on shop windows. The one time I venture to take a picture of a door with Kenyan graffiti on it, I get my wrist wrung by a butcher. I am taken aback and tell him that I am not taking a picture of him. Abasi intermediates for me. The man refuses to let go and wants to look at the picture on my phone. Even after I show it to him and proceed to delete it, he is not convinced. Abasi tells me it is because he is frightened. A lot of people are superstitious and believe that a photograph can steal their souls. Ah! I should have thought about that. Happens, or used to happen, in India too. Abasi talks some more in Swahili to reassure the butcher, and finally we walk again.

A number of girls on the way say “Sasa!” (hi!) to Abasi and stop him to chat. He is quite the popular man. He tells me that many of them would like to say hello to me, “in a good-natured way only”, but he is telling them to not pester me. This partiality in treatment, even if meant just as courtesy for a guest, makes me wonder who actually creates the divide – the outsiders or the slum-dwellers.

We cross the railway track. On both sides of it, are –smiths of all kinds. The track is on an elevated level, and you can see all of Kibera from this vantage point. There are discolored corrugated tin roofs looking up at us from everywhere. At one far end, painted in big block white letters on one of the biggest roofs is ‘Kibera Health Clinic’. This was built by some Scandinavians. We are going to walk in a loop now, descending from one end into the ‘valley’ and coming back up from another to the track.

As we walk, I see many shops – rice, sorghum, maize, small mom and pop stores with everything, bananas, wood, and even a kiosk which sells USB drives. Of course, there are as many green M-pesa agents’ shops as there are Starbucks cafes in any self-respecting developed city. One every 20 feet literally. It is not surprising because you can pay using M-pesa at the smallest of shops. However, not every shopkeeper has an M-pesa till number. This is a code that they need to buy with a small amount of payment every day to Safaricom so that customers can pay them with M-pesa. When the customer enters the code and an amount on her phone, that money is deducted from her M-pesa balance and credited to the shopkeeper’s M-pesa account. If the till number is not renewed daily, the shopkeeper cannot transact with M-pesa. This is something I need to come back and probe, to see if M-pesa is actually used for trading goods and services, beyond remittance-like transfers. I am thinking of interviewing about 20 Kibera consumers (ordinary people) and micro-entrepreneurs (tailors, locksmiths, ironsmiths, plumbers etc.) and 20 M-pesa agents, but need to think through the robustness of such a research plan.

M-pesa agents fascinate me. I don’t yet properly understand their role in this economy driven by mobile money. Here’s what I got out of speaking with one of them in Kibera. The way the system works is that the M-pesa agent first deposits liquid cash with Safaricom, which then credits his mobile phone with the same amount of M-pesa. Let’s say he deposits 1,000 units with Safaricom. Now, say you go up to the agent, and deposit 100 units of cash for 100 units of M-pesa on your mobile phone. Safaricom debits 100 units of M-pesa from the agent’s account and credits it to your account, and your 100 units of liquid cash is pocketed by the agent in return. So, the agent works as a completely independent micro-ATM. If he expects a large number or shilling value of M-pesa transactions, he can choose to deposit a greater amount of money with Safaricom to support the demand. It all depends on how much liquidity he can forego to begin with, which begs the question – is it only for those in Kibera with deep pockets?

I ask Abasi and the M-pesa agent, how do customers choose which agent to go to? Isn’t the competition too high with so many of you within breathing distance of each other? Or, like the Starbucks model, do people go to the nearest one? Starbucks’ retail strategy pre-recession included opening up cafes on opposite sides of a street, because consumers suffer from so much inertia that they don’t like crossing streets, especially if there’s a traffic light. Abasi explains that customers find an M-pesa agent they trust and then make repeat visits to them, so relationship building with customers is very important. In all of this, I realize that Safaricom basically functions as a one-time ‘holding’ party, taking cash the first time around from the agent. After that, it is just moving M-pesa around from the agent to the customer, and so forth. Small changes in liquidity and dealings in cash are all on the agent, rendering her with a lot of power. If she ‘forecasts’ the demand accurately and has the liquidity (=supply) to match it, she can make some nice money in the form of commissions from Safaricom. Another interesting thing I found out is that Safaricom gives the agent more commission for the quantity of transactions, not the value of transactions. This strategy is something I need to understand better.

After agonizing over how M-pesa works, we walk to Abasi’s old house. Dwellings all around us are made of clay and supported with wooden sticks. Abasi points out to me communal showers on the way, which cost 10 shillings per use. Then, we go to his current house, a place built of brick and cement. I ask Abasi if he would be considered better off than most others in Kibera, and he says he would be “middle class” here. I am surprised because I have not seen too many other houses built with solid construction material. He also has a dog, as malnourished as it is, and a kennel for it. His one-room apartment is about 10 feet by 8 feet (as big as my Blakeley room, strangely enough). It smells of stale ugale and sweat, like many boys’ rooms back in undergrad, I must say. This may be due to different circumstances of course, but hey, I am just trying to lighten up the mood here.

We finish the loop, run into a few other people, and finally walk back to my house for lunch.

Sasa from Nairobi!

Hello! My name is Anisha. I am a first-year graduate student at The Fletcher School and a Blakeley Fellow in 2014. This 'summer' (technically, it is winter where I am, south of the equator), I am spending my summer in Nairobi, Kenya conducting research on the impact of m-commerce in addressing some of Nairobi's most pressing urbanization challenges.

Let me tell you a little bit about myself first to set the context. I am from India, but have spent close to nine years studying, working and living outside the country. Most recently before Fletcher, I lived and worked in Singapore. At Fletcher, I am pursuing a master in international business, with a focus on strategy consulting, international finance and technology in development. You can read more about my background here if you are interested.

Coming into Fletcher, I was very keen to put my private sector experience to use in frontier markets. Having spent time in sub-Saharan Africa in 2009 as a Teaching Fellow at the Meltwater Entrepreneurial School of Technology in Ghana, I was interested in coming back to Africa. The Blakeley Fellowship gave me the the opportunity to pursue my career interests, and long story short, I landed up in Nairobi!

My research in Nairobi explores the innovative potential of m-commerce in bringing about fundamental change in issues of sanitation, water, transportation and retail in this rapidly urbanizing city. The questions I hope to answer at the end of the project are:

(1) While a lot of solutions are coming up via the mode of m-commerce, are they providing only symptomatic relief or actually creating long-term change?

(2) Who is spearheading innovation - small and medium enterprises, corporate players, public sector and/or NGOs? How is the government engaged and being engaged in these efforts?

(3) Who are the beneficiaries - low-income, middle class and/or high-income?

I am doing this research under the aegis of the Institute of Business at the Global Context or IBGC at The Fletcher School, with support from Mastercard Worldwide. Needless to say, there are a lot of knotty issues to think about as Nairobi urbanizes at a fast pace. Income and wealth inequality, governance, urban planning, infrastructure including but not limited to information and communication technologies (ICT) and human capital are but just a few.

I have now been in Nairobi for about two weeks. My research methodology involves conducting in-depth qualitative interviews with stakeholders from a variety of organizations including tech startups, corporate players, government, public sector, academia and consultancies. Of course, these interviews need to be structured in a manner that we can draw conclusions and insight in our analysis. Additionally, there is extensive desk research akin to a literature review that I am doing simultaneously. My fieldwork is estimated to be spread out over eight weeks, and in the two weeks so far, I have learnt some very interesting things.

I will report back with preliminary findings after some analysis (to the extent that I can share on a blog before the research is published :)), but here are a two of my broad takeaways:

(1) There is a tremendous amount of innovation coming out of Nairobi, but it is overwhelmingly focused on smartphones. This is not to say that "dumb" phones or basic feature phones are not getting connected to the throbbing pulse of trade and business in the city, but it is still limited. These observations come from a field trip of Kibera, Kenya's largest urban slums, where I interviewed several micro-entrepreneurs. As a corollary - and this is a hypothesis at this point - it would appear that beneficiaries are mainly from middle-income and high-income groups. It would be hard to say that the base of the pyramid is disadvantaged in a context where we are talking about a low-income country to begin with, and this stage of development, any income growth is a prerogative over addressing income inequality, but there is strong reason to probe whether low-income consumers are part of the growth story. Especially as I read Thomas Piketty's mind-opening book on the rise of income inequality that capitalism promotes (or at least does not negate), I find myself delving into question repeatedly.

(2) Safaricom - the leading telecom company in Kenya with a market capitalization worth 27% of Kenya's GDP - has engineered a revolution in how money is transacted by making it possible, easy, affordable and commercially viable and is at the forefront of catalyzing change. M-Pesa, their mobile payments system, is largely behind the transformation of Nairobi into a m-commerce leader. It is also a fundamental platform for most m-commerce businesses to convert consumer demand into real purchase. Having said that, m-commerce ideas have taken a life of their own, and are evolving in a very distinct manner that encourages consumption as opposed to plain vanilla savings (which is what M-Pesa was started to enable).

(3) I will also include a question here masquerading as a takeaway. I started out with the idea of understanding whether m-commerce driven change was having long-term or short-term impact, but I realize the need to think about whether it matters? In an environment where "smart" planning and execution is so far from reality, perhaps thinking long-term is not the solution. Perhaps, short-term solutions can create more tangible impact.

All in all, it looks to be an exciting summer, with a lot to learn about private sector development, entrepreneurship and technology in one of the foremost frontier markets in Africa.

Exploring & Experiencing the Pearl of Africa

As I write this, I am quickly approaching the end of my first full month in Uganda. By now I have settled in quite well at my guesthouse in Kampala, attended a local wedding and traveled to over 9 districts in Northern Uganda; it seems unbelievable that up until a few weeks ago I had never been to Africa!.

I arrived Kampala in May with a mixture of anticipation and apprehension. On my ride from the airport I noticed that Kampala was very similar to Kathmandu (my home town in Nepal) at first glance. Both are surrounded by hills and every road has ample potholes, street vendors, not-so-cautious motorcycle riders, and similarly lined rows of shops along main roads with advertisements painted for Coke, Pepsi or telecom companies. It felt good to be ‘back’. Since then comparing Uganda with Nepal (albeit superficially) comes naturally to me; there is less deferential here…women ‘seem’ relatively more empowered…people are equally laidback…sodas and food cost twice as much etc. Generally though, Uganda is similar to Nepal in that the truly poor population does not have nearly enough and the truly wealthy have way too much. In Uganda this gap seems slightly wider, as Nepal has a relatively larger middle class, but the principles of disparity are there and our countries are suffering for it. .

In the days following my arrival, I began my work as a Consultant for FIT Uganda, an agri-business consulting firm. The work includes assessing the implementation of Farmer Record Management Information System (FARMIS) in North Uganda, and providing recommendations based on the assessment to facilitate delivery of enhanced results. FARMIS is an innovative project that provides farmers with market information and intelligence, financial literacy, as well as a web and mobile-based farm record management capabilities. My trip to Northern Uganda was a part of this project. We met and interacted with over 300 farmers. I am now working on financial linkages component of the project for which I have presented a concept note that proposes a framework on access and use of credit by farmers that links them to the formal financial system. Additionally, I am also contributing to and editing the Market Analysis Report, an annual national agri-market analysis publication of commodities in Uganda. Before my time ends here, we are working to outline the design of a financial literacy program in partnership with Mercy Corps, GIZ and Bank of Uganda. The program is intended to provide farmers in rural Uganda with financial management and educational information through SMS and radio. .

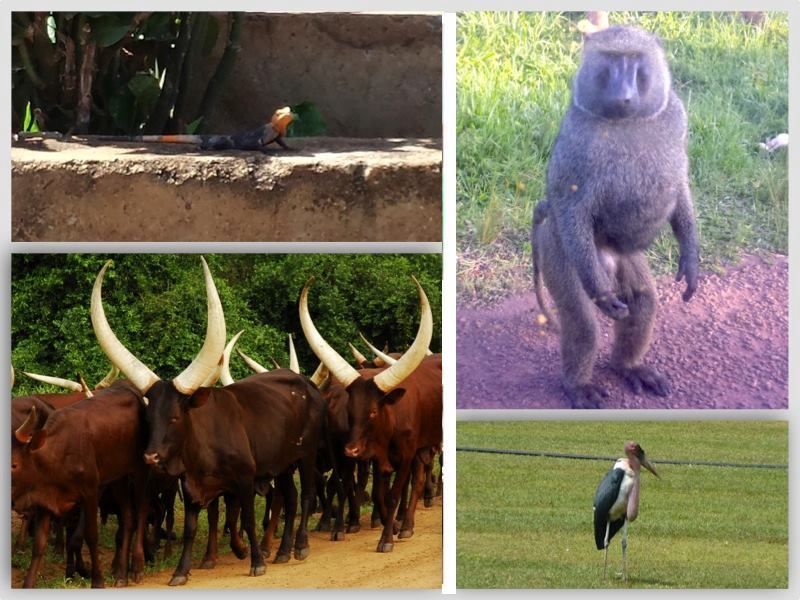

Everything is coming together well! All in all it is shaping to be a productive and a fulfilling summer. The night is coming to an end so I’ll leave you with some pictures: .

.

Live from South Africa

Hi! My name is Braden. I completed my MBA at IE Business School in Madrid and two of three semesters of my MALD (master of law and diplomacy) at The Fletcher School at Tufts University. Before graduating in December of 2014 I am spending this summer doing an internship in Jozi (as locals call it). I was fortunate enough to be awarded a Blakeley Foundation Fellowship to support my participation in Emzingo, a social impact leadership development program. Emzingo seeks to build socially responsible leaders by bringing together a group of MBA and policy students for leadership training, field immersion (i.e. being in South Africa), and social impact consulting.

We are a group of 17 people from 7 nationalities hailing from masters programs in the US, Europe, and Canada. This week was orientation and tomorrow we begin working on our projects; each project has a pair of students. I will be working on a project with a wonderful woman from the UK, Lavinia, at Endeavor South Africa, a high-impact incubator. It is an extraordinary program and this week has been a whirlwind of excitement – I will provide some of the highlights from the country and program.

We began by getting settled in our apartments located at University of Witswaterand, Johannesburg leading university. The apartments are like a large dorm room with a kitchenette, desk, bathroom, and are fully furnished. We also get a rental car for each team. The first night we went to a great restaurant to celebrate and get to know each other where we ate tons of great meat – what South Africa is known for. Throughout the week we had a range of events that include: a tour of the city, visit to the Apartheid Museum, seminar with a Wits Business School professor, leadership seminar, life-reflections group session, cultural awareness seminar, and lots of lunches at great places. Friday we spent the day with Coca-Cola Africa’s Director of Sustainability where we learned about some of their efforts to do responsible business. This included a trip to a school they built in a rural squatter camp. Saturday we toured Soweto where we visited Kliptown Youth Program, which won the CNN Hero award for its education program in the slum. Afterwards we went bungee jumping off Orlando Towers, a regeneration project in Soweto. Sunday a group of us went to a reserve about an hour and half out of the city to play with baby lions. All-in-all a pretty epic start to the Emzingo program.

Among all the cool events we took time to understand the history of South Africa, which I knew little of. It truly is a miraculous country with many lessons to share with the world. Mandela was a tremendous leader who guided the country through a transition that by if you had asked any political scientist should have been a civil war. It is also amazing that apartheid existed so recently, and reminds us of how real the threats are that still exist. Among all this it is striking how many black South Africans are rising up to be the middle class. Having spent time in Kenya I was struck at how the “bar” for poverty here is, on average, much higher than in Kenya. After only a week I can understand why South Africa is a lighthouse on the shores of Africa, guiding the continents way.

Thank you Mr. Blakeley for making this possible!

¡Hola de Kilimani!

It is hard to imagine that here, in the heart of Kilimani, Señor Pete is pumping out California-quality burritos. But it’s true. The small Mexican café gets started early. As customers line up for their morning chai ya maziwa (the local milk tea), Pete’s staff is busy making tortilla dough and smashing farm fresh avocados into a tangy guacamole. Located on the ground floor of the iHub, Pete’s is just one of many strange juxtapositions I have come to know during my first few days in Kenya. While an authentic Mexican restaurant in Nairobi indeed seems odd, at further examination Pete’s success actually makes sense. The café is truly representative of Kenya’s unique blend of east and west—and underscores the country’s multicultural vibe and grand global ambitions.

It is hard to imagine that here, in the heart of Kilimani, Señor Pete is pumping out California-quality burritos. But it’s true. The small Mexican café gets started early. As customers line up for their morning chai ya maziwa (the local milk tea), Pete’s staff is busy making tortilla dough and smashing farm fresh avocados into a tangy guacamole. Located on the ground floor of the iHub, Pete’s is just one of many strange juxtapositions I have come to know during my first few days in Kenya. While an authentic Mexican restaurant in Nairobi indeed seems odd, at further examination Pete’s success actually makes sense. The café is truly representative of Kenya’s unique blend of east and west—and underscores the country’s multicultural vibe and grand global ambitions.

Beyond burritos, this global outlook is apparent throughout Bishop Magua Center—the office block where both Pete’s and Ushahidi (my employer for the summer) are located. Several years ago Ushahidi launched the iHub, a tech workspace and innovation hub aimed at empowering Africa’s next generation of technocrats. Following iHub’s lead, many other organizations set up shop at Bishop Magua including the Praekelt Foundation (an incubator for mobile technology which improves the health and well-being of people living in poverty), FrontlineSMS (a text-based software provider), and a branch of GSMA (an alliance of mobile network operators). Besides these big names, smaller start-ups are making noise. M-Farm, farmforce, Savannah Fund, and many other micro-entrepreneurs building mobile apps and games are located right here in Kiliamani.

Clearly, the iHub and others have sparked a bit of a revolution here in East Africa. Not a day goes by without a new article proclaiming Kenya’s emerging tech sector and promise of growth. Nairobi’s been called Silicon Savannah with high hopes of transforming Kenya into an economic powerhouse. With this growth comes the possibility of high-paying jobs and strong opportunities for professional advancement. It is indeed exciting—and I feel privileged to play a very small part this summer through my fellowship at Ushahidi.

So next time you bite into your Chipotle burrito, think about its brother being consumed at Pete’s, working to fuel the talented, innovative young minds at Bishop Magua Center. Call it growth by guacamole or burrito diplomacy, either way economic advancement and additional foreign investment is certainly in Kenya’s future. You can read more about my summer in Nairobi here at my Tumblr: http://nairobridge.tumblr.com

Lima's entrepreneurial landscape

The main reason that brought me to Peru was to learn and find out more about the stage of their entrepreneurial ecosystem. According to the Global Entrepreneurial Monitor (the most relevant publication about entrepreneurship) Peru is one of the most entrepreneurial countries in the world.

The main reason that brought me to Peru was to learn and find out more about the stage of their entrepreneurial ecosystem. According to the Global Entrepreneurial Monitor (the most relevant publication about entrepreneurship) Peru is one of the most entrepreneurial countries in the world.

I have learned a lot since I arrived. I have met all types of entrepreneurs. Some more related to the definition most of us have from the American schools, but others do defer and even challenge our definition of entrepreneur. However, in most cases this difference does not stop them to feel part and work towards the improvement of their entrepreneurial ecosystem. At the end of the day an ecosystem is made up by people, so that is what we need, passionate people willing to share ideas and make things happen.

I also find out there are several international organisations with a heavy presence in the country:

Wayra

Telefónica's global startup accelerator. It established a presence in Lima in 2011. Twice a year they elect 10 teams with the best Internet related business ideas. Each team receives the equivalent to €40,000 plus office space and most importantly: mentoring.

NESst

An NGO that has the mission to develop sustainable social enterprises that solve critical social problems in emerging market economies. NESst established in Peru in 2007.

The feedback I often heard from the entrepreneurs is that it is hard to find a place to start working with their startup idea. Rents are quite expensive and contracts are made for at least one year. Entrepreneurs most of the time are not willing to invest the little money they have on working space.

This is the reason why the Peruvian landscape has seen in the last year a proliferation of co-working spaces. However there is a need of more!! (this is obvious when one enters any Starbucks in Lima and finds the place packed with more computers than people).

On the other hand there is a feeling that something is changing in Peru and that the economic growth is already giving some payoff. People feel the entrepreneurial is about to boost in the years to come.

As part of my work here in Lima we are building a network of entrepreneurs that have already achieved a success with their endeavours. The idea is to use them as example for others to come. This coming Wednesday (4:30 pm Boston time) we will be broadcasting live through YouTube an event that is looking to highlight the positive and negative aspects (and how to overcome them) of the Peruvian entrepreneurial ecosystem. Even though the event will be held in Spanish it would be great if you could join for support. I hope this will be the first of many more conversations that will help build a stronger and better ecosystem for the entrepreneurs in Peru.

If you like to join, on the day of the event you will be able to find the link to the YouTube channel to watch the broadcast at this Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/aninnovationred

Finally! More Photos from Chad

The charcoal production site: The manioc paste is then mixed with carbonized agricultural material. This material was left out in the rain and the team was trying to dry it out.

Here is the sack of manioc (also known as cassava or yuca). The chunks in the picture are first pulverized into a flour and then flour is stirred into a big pot of boiling water until the mixture becomes a sticky paste.

The charcoal production site:

The charcoal production team:

Here is the sack of manioc (also known as cassava or yuca). The chunks in the picture are first pulverized into a flour and then flour is stirred into a big pot of boiling water until the mixture becomes a sticky paste.

The manioc paste is then mixed with carbonized agricultural material. This material was left out in the rain and the team was trying to dry it out.

Pouring the prepared binder mix for another batch of briquettes:

The carbonized material is mixed with the binder and then pressed into these molds. The team can produce about 1300 briquettes in a 7.5 hr workday.

Drying the briquettes on a tarp. The thin plastic tarps costs about $50 each in Chad.

Quick! Move the briquettes before the storm hits! Deluge occurred minutes later...

Taking measurements of wood charcoal to compare with our briquettes.

Eating food cooked with the eco-briquettes.

Within sight of our charcoal production, locals passed by riding bicycles with huge bags of charcoal strapped to the back. They smuggle charcoal into the city by dirt roads and paths to avoid the checkpoints on the main roads.

David talks business, management, and strategy with Aquilas, the Chadian National Coordinator. The daily long conversations were critical for building relationships and talking through the challenges together.

David and Ghislain logging onto the new laptop donated to ENVODEV by a great friend in Boston. Thanks Nate!

Studying the design of the rammed-earth mold. We discovered several errors in the instructions. Thankfully we were able to adapt.

Aquilas had previous experience ramming earth. He put us all to shame! My hands were covered in blisters after an hour of swapping turns packing the clay.

Some of the local kids thought I was Chinese. The only non-Africans they had ever seen were the Chinese oil workers.

The finished rammed earth stove! We finished this on the last day in Moundou. Grateful to have finished one before we left!

ENVODEV's full-time staff: Ghislain, Aquilas, and David.

Ghislain and I posing for a picture in Moundou. It was so great to get to be a part of the team!

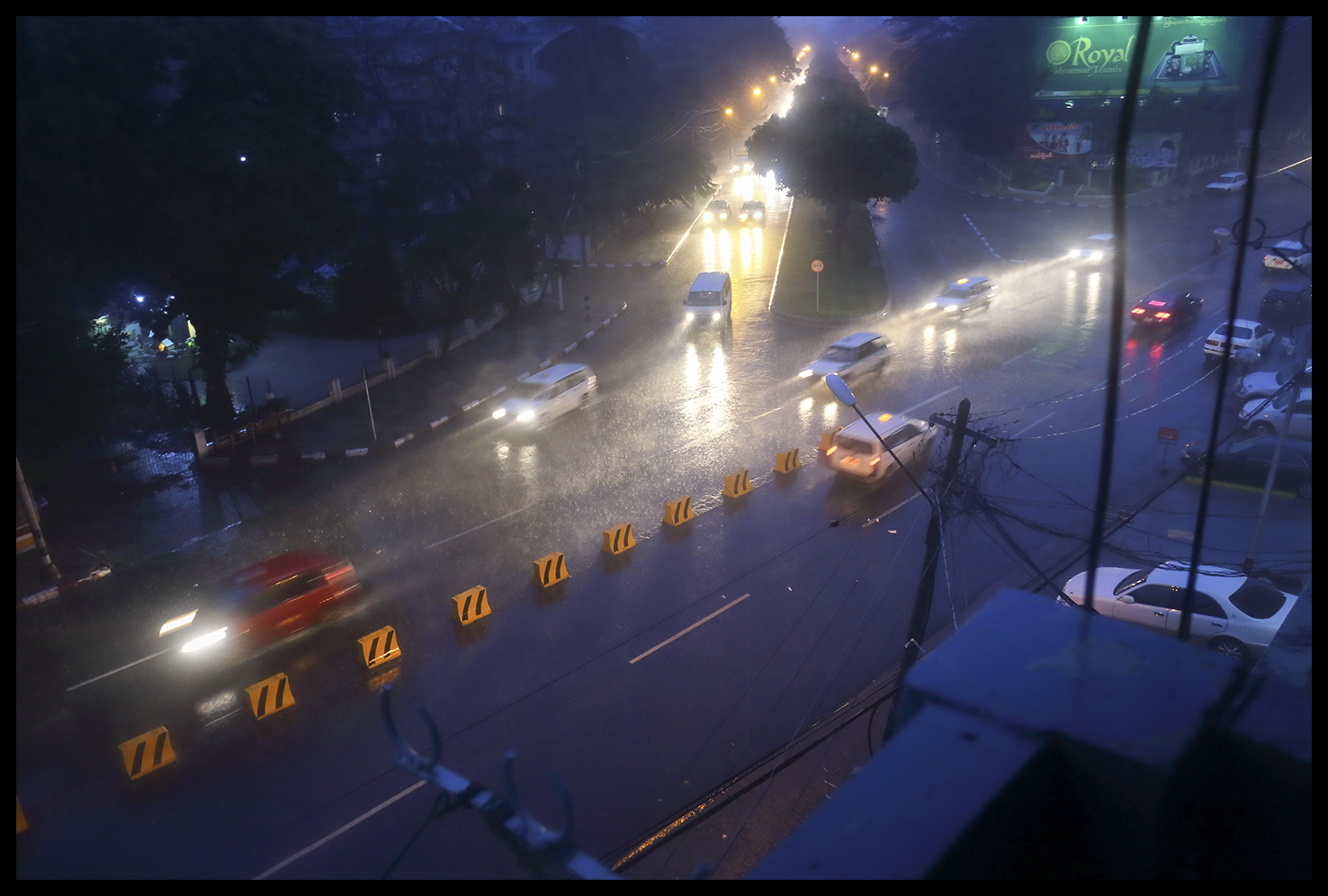

Myanmar: Building Hope from Rubble

[p]U Aung Zaw, whose business prior to April 2008 employed 43 workers and could produce anything that you could draw, from elaborately colored platters to wine decanters with cleverly placed pockets for cooling ice. A simple factory built from timber and sheet metal didn’t meet the standards of the 1st world, but served many businesses, organizations, embassies, and individual homes throughout Myanmar. [/p]

[p]However after Nargis the plant was destroyed, there was little hope of rebuilding and zero support for small businesses or industries impacted by the disaster. The kiln which had been the centerpiece of the factory had been cracked in the storm and because of the building’s collapse, was almost beyond repair. Hundreds of shelves of finished and nearly finished products were scattered around more then an acre of jungle, itself now reduced to a chaotic jumble of branches, frawns, timber, and sheet metal. Charcoal, which had been the primary fuel source for the furnace, climbed rapidly in price to nearly 12 times the 2008 costs. And with no income most of the skilled glass workers quickly left the compound to work abroad.[/p]

[p]In addition a larger problem looms with the remaining former employees. For families that didn’t leave, they took up residence on the factory’s property and have taken work at other businesses or work as day laborers. Having lost all paperwork in the cyclone, U Aung Zaw could not prove the title to his land, and faced both social and physical resistance when he voiced his resentment of the small shanty town that has taken over part of the old factory grounds.[/p]

[p]Small fights have broken out, and now as they come home former workers and their families will take items from the piles around the old compound to use or re-sell. U Aung Zaw refused to speak about the subject further given his fear of physical harm and retaliation, particularly if he were to push to rebuild the factory or to have the squatting homes removed.[/p]

[p]As a testament to U Aung Zaw and his family’s ingenuity, it became apparent that slowly returning tourism might offer some small income. So to provide for the family’s income U Aung Zaw would allow visitors to wander the grounds of his compound, digging through deep piles of frawns and mud to unearth largely unbroken glassware. A literal treasure hunt would turn up anything that had been in production prior to the cyclone, and for those who are more creative, U Aung Zaw’s family would cut down, polish, and even fuse pieces of glass to make entirely new items.[/p]

[p]This leaves me asking a question I really don’t know how to answer: Regardless of funding or resources, how do you work through suffering, trauma, and loss? How do you find a way to support and assist when an internal desire has gone out?[/p]

[p]Many of you who know me are probably aware of how much I’ve considered this question of behavior and psychology to be of crucial value. I imagine that to make an impact in these situations it would need to be of central importance to any approach to provide support and must specifically begin with conversations and a lot of good listening. And still, sadly, at times it seems you just have to accept a result and mitigate pain and suffering by moving on. But where does that cut off exist?[/p]

[p]I’ll be visiting the former factory again with a local Burmese art gallery/social enterprise, and will update as the story unfolds.[/p]

A Village Stay in Burkina Faso

While I've been busy at work in Ouagadougou, capturing many of the interviews I conducted with beneficiaries of the Agricultural Development Project of the Millennium Challenge Corporation Compact with Burkina Faso, and writing reports from my field visits (more on this soon), I wanted to share with you all some photos from a recent visit to a village in western Burkina Faso. Last weekend, I had the good fortune of accompanying a co-worker to his village near Doudou, where he served during his time as a Peace Corps Volunteer. Doudou is approx. 150 km from Ouagadougou, near Koudougou, the third largest city in Burkina Faso (after Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dialosso). ("Dougou", I recently learned, means "ville" or town).

While we only stayed a night, it felt like a long weekend, filled with special moments: sharing a meal with former counterparts, visiting different homes to pay our respects, inspecting a newly installed water pump, sleeping under the stars, and strolling through the market in Doudou on Sunday.

Sharing an incredible feast with my co-worker's former counterpart, Moises

Visiting the local market in Doudou on Sunday (Photo credit: Chris)

The local language, Lyele, was as enjoyable to learn as Wolof, and while I only was able to pick up a few phrases, I know fellow Star Wars fans would have been absolutely enchanted.

Me: "Aja?"

Woman in Market: "Jawane!"

Literally, this means, "Do you have the force?" and the response, "Yes, I have the force!"

Many come to the market on Sundays after church (usually a 3-4 hour service), and sit under the wooden stalls for some shade, drinking dolo, the local brew made from fermented millet, and catching up on the local gossip. The dominant ethnic group in the area is Gurunsi, of which most are Christian.

One of the best parts of our stay was our lodging. Traditional style homes are large adobe constructions that have a small wall around them. They can typically hold at least a dozen people, usually more. This particular encampement, is one of four in Burkina Faso, and is a community-organized and supported endeavor. Profits go towards local projects, such as a local primary school, an adult education center, and family planning classes for women. The manager of the compound also had a strong agro-ecological philosophy, detailing why many in the area were committed to organic compost and avoided using chemicals, as the community had already experienced the negative health side effects agrochemicals could cause if not properly applied.

Due to the heat, we placed our beds outside and it was a smart decision. The stars at night were absolutely incredible.

All in all, it was an incredibly enjoyable weekend, and a nice break from the bustle of Ouaga.

A few more photos from our village stay:

Exploring the entrepreneurship trail in Lima

Even before I set a foot in Lima I was warned not to expect to enjoy a sunny summer, that in fact the temperature was going to be constantly around 60°F (15°C) day and night and with a humidity of 85% or more. Unfortunately that was not a lie! Almost every day is cloudy and somewhat cold, nothing compared to Boston (of course), but still quite chilly.

However, I was never told about and was not really expecting to see, so many parks, full of flowers and with very well taken care lawns. Public spaces are a high priority for many municipalities in Lima and Peruvians (as well as Peruvians cats!!) do take advantage of these spaces. Internet is even offered for free not only in parks but also in metro stations and many cafeterias and restaurants.

I have been studying about the history of its public transportation because I have been helping to organize an event where understanding Lima’s future infrastructure plans is very relevant. Can you imagine a city of more than 8 million people with a single metro line that crosses the city from south to center? The center to north leg is not even completed yet (it is part of the second phase of the metro line number 1).

However, besides the unfinished metro they do have a modern BRT system, which is also only running south to north. In my experience, the BRT has proven to be very useful and fast. The city of Lima, similar to others in the world, has heavy traffic almost at any time of the day or night.

Infrastructure plays a very relevant role in the developing of an entrepreneurial ecosystem. My interest in understanding more about this particular ecosystem is what brought me here to Lima in the first place. So I was initially concerned about how is that an entrepreneurial spirit can flourish in a space that is not very well connected.

It did not took me long to be impressed about the Peruvian entrepreneurial spirit. It was first palpable in the quality and diversity of its cuisine (they even have made a fusion style between Peruvian and Chinese cuisine called “chifa”). Not only every dish I have tried is full of flavor but also it is admirable the care Peruvians put into the decoration and image of their restaurants, even at the small places that only offer set meals. Peruvians are very proud about their cuisine and are not shy to show it in every detail, the menu, the dish presentation and even the boxes or bags used for take away meals.

I am working now in learning how could this entrepreneurial spirit be spilled in other realms and not only in the food sector.

The people I am working with want to bring The Hub brand to Lima, because they believe there is urgency for a collaborative space that is able to offer mentorship and financial support for the new wave of social entrepreneurs that are starting to emerge.

This is a live project! I will let you more about it in a few more weeks!

Let me just share with you some amazing landscapes of the city of Lima.

This archeological site (Huaca Pucllana) is located in the middle of the city.

Myanmar: a few stories

[p]The research we’ve been conducting on financial habits in rural and urban communities has moved relatively smoothly despite several hang-ups, which I’ll describe in a later post.[/p]

[p]We’ve encountered some truly incredible people, and in every case our interviewees have been generous with their time and insights regarding how they approach finances in their lives. As we’re not building a quantitative picture, instead relying on the personal observation and insight from individuals, we’ve had more work to do in sifting through our conversations and giving an order to what we’ve heard and learned. Here are a few profiles of people we’ve talked to so far.[/p]

[p]Early on we spent time with Daw Boke who jointly operates an apartment rental service and a bus ticket sales business from her home with her husband. Aunty Boke, as she’s affectionately known, has slowly built up her business in downtown Yangon from the home she’s occupied for the last 40 years. As buildings grew out of the old traditional wooden homes – first bland socialist era apartments, and now glitzier structures built by Chinese, Thai, and Singaporean investors – she has grown extremely familiar with the property and apartment owners in the area. In Myanmar it is still illegal for 100% foreign ownership of property, so she her business has been entirely with Burmese individuals.[/p]

[p]Over the last two years of the reform Aunty Boke’s business has grown rapidly. Over five years ago apartment turn over and rentals were relatively slow and she relied on her landline phone as a second source of income. Most homes don’t have phones so private phones that are set on the sidewalk on a small children’s table, or beside a front door effectively become public phones for a small fee and can bring in much needed extra money. However that business all but dried up for Aunty Boke over the last two years as cell phone use has grown rapidly.[/p]

[p]Now Aunty Boke’s apartment business provides the lion’s share of income by connecting individuals with apartment owner’s spaces. However her reputation and length of time working in this field has made her a familiar source for successful rentals thus allowing her to work directly with apartment owners, and earn a larger portion of the profit from a rental. Normally the renter's fee is divided between anyone who has interacted in the process of renting an apartment – for example if you unlock the door for a client or show them where the apartment is you get a certain percentage of the renter’s fee. Interestingly too all transactions for rentals occur in cash. If Aunty Boke helps sell an apartment – at shockingly high prices now as the Myanmar real estate market has exploded – the buyer will meet the owner at the apartment with hundreds of millions of dollars in cash, carried up dimly lit stairs in trash bags. This process is surprisingly easy and completely normal. Services exist for carting large volumes of cash around – a curb side pick up and drop off service. She told us stories of how people would forget bags of cash in taxis, or on curbs, would walk up to their apartment realize their error, and run back down to find the bags sitting in the same place, or the cab driver trying to find them to return the bag. This does not mean crime doesn’t occur – she noted that just several days prior a car was broken into on her street and emptied of its contents (though there were no bags of cash inside).[/p]

[p]Despite a high cash system of transacting in real estate, and the use of a bank, Aunty Boke confirmed a trend we’ve seen repeated in a wide range of economic segments -She invests in a friend's business (car parts manufacturing) just so she won’t have large volumes of cash in her home or in the bank account (which she only opened 3 months ago). While she does use banks, multiple economic crisis and the collapse of several former banks leaves her wary, so she prefers to bank with the government banks that have more state guarantees than the private ones.[/p]

[p]When looking at financial habits, after 60 years of military rule it's impossible not to run square into those who’ve suffered under that reign. Political prisoners have to transact, make money to survive, and try to live as best they can given a system stacked against them. But what is striking is the perseverance and generosity they demonstrate in overcoming years of imprisonment. In another encounter we met with a former political prisoner, Ko Kyaw Soe, who after his release from prison, worked as a taxi driver, and provides interest free loans to other former political prisoners to start small businesses.[/p]

[p]Ko Kyaw Soe is by no means rich. He lives in a small second floor apartment that over looks the street where he parks his car. Out of prison a year ago, he still must take time off from driving due to kidney injuries he sustained from torture by prison guards. But for this exact reason he and two other former political prisoners now use their incomes to provide loans to those still coming out of prison. By saving up the equivalent of a little more then $500 they are able to help the discharged political prisoner start a small business or place a rental down payment on a taxi. They then have a year to repay the amount.[/p]

[p]Cars, which have been notoriously expensive, still are commodities that most taxi drivers do not actually own. However prices have come down significantly – only three years ago a basic Toyota that could cost $600,000 due to the import license and drivers permit, now are down to $100,000. Ko Kyaw Soe owns his own car but most of the prisoners starting out must pay for a daily rental fee, gas, and larger monthly costs to the car owner.[/p]

[p]Ko Kyaw Soe, given his political status, cannot directly transact in the bank account system. When arrested in 2007 he lost a large amount of his money to the government. Instead he keeps the cash in his car – safe compared to his home, which has seen frequent ‘visits’ by the police. Here too, all of his transactions are made in cash from the rent of his house to providing funds to the other prisoners. Cash, though at risk of theft, is liquid and easy to transact in, which is crucial in a field that has a high cash turnover rate like the taxi business. Despite the risk, he hopes that by providing loan to other former political prisoners they will provide a leg up for those have been stigmatized by years of imprisonment.[/p]

[p]I’m hoping to post more profiles of people we’ve interviewed and some photos too if possible. Eventually we’ll have a few more concrete ideas about just what issues people face, how they adapt, and some factors unique to Myanmar’s context.[/p]